Peter Hebblethwaite, NCR’s late Vatican correspondent, subtitled his excellent biography of Giovanni Battista Montini, Pope Paul VI, “the first modern pope.” By “modern” Hebblethwaite meant that he was the first pontiff to embrace the 20th century and jettison the trappings and pretensions of the absolutist post-Reformation papacy. There’s truth to this, but I’d rather give the honor to Pope John XXIII, who described Montini as “un po’ Amletico” (a bit Hamlet-like). Just as the prince endlessly hesitated to avenge his father’s murder, so Montini was wavering, indecisive and ambiguous.

He even asked himself, “Am I Hamlet or Don Quixote?” This is the key question for an assessment of Paul VI’s papacy. Were there too many compromises and half-decided issues?

Born in Concesio, Italy, in 1897, Montini was the son of an upper-class newspaper editor, lawyer and member of the Italian parliament. From 1922 to 1954, except for a brief stint in 1923 in Warsaw, Montini worked in the Vatican Secretariat of State, while doing part-time pastoral work with university students. From 1937, he worked closely with Eugenio Pacelli, later Pope Pius XII.

A moderate progressive, Montini was anti-fascist, pro-democratic and widely read in French social philosophy, especially that of Jacques Maritain, who had great influence on Catholicism in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, shifting it in a genuinely democratic direction.

Montini was also profoundly influenced by the French thinker Jean Guitton, who worked to reconcile faith and science, but who moved in a conservative direction after the Second Vatican Council. The future pope often corresponded with these and other influential thinkers.

After 20 years in the Curia, he had gained many enemies, and in the declining years of Pius XII in the early 1950s, Montini fell foul of a reactionary rump of cardinals who believed he was “too liberal.” They used a minor incident, which was inflated into “concealing information from the Holy Father,” to get rid of him. In November 1954 he was appointed archbishop of Milan, but was not made a cardinal; he had actually turned down the offer of a red hat in 1953.

A large, complex diocese, his nine years in Milan gave him the pastoral experience he lacked. Between 1951 and 1962 he traveled to the United States twice, Ireland and seven countries in Africa. In December 1958, John XXIII made him cardinal. He participated in preparations for the Second Vatican Council, but during the first session in 1962 he seemed unenthusiastic and only spoke twice.

John XXIII died June 3, 1963. The Second Vatican Council was really just beginning, so this conclave was one of the most important for centuries. The anti-conciliar reactionaries settled on a former nuncio to Spain, Ildebrando Antoniutti, as their candidate, with Montini supported by moderates and progressives.

There was a dramatic scene in the conclave when Cardinal Gustavo Testa angrily accused the Antoniutti faction of obstruction. Montini, fearful of being a cause of division, started to get to his feet to renounce his candidacy. He was grabbed by Cardinal Giovanni Urbani, who dragged him back to his seat, muttering, “Eminenza, Lei stia zitto! [Eminence, shut up!]”

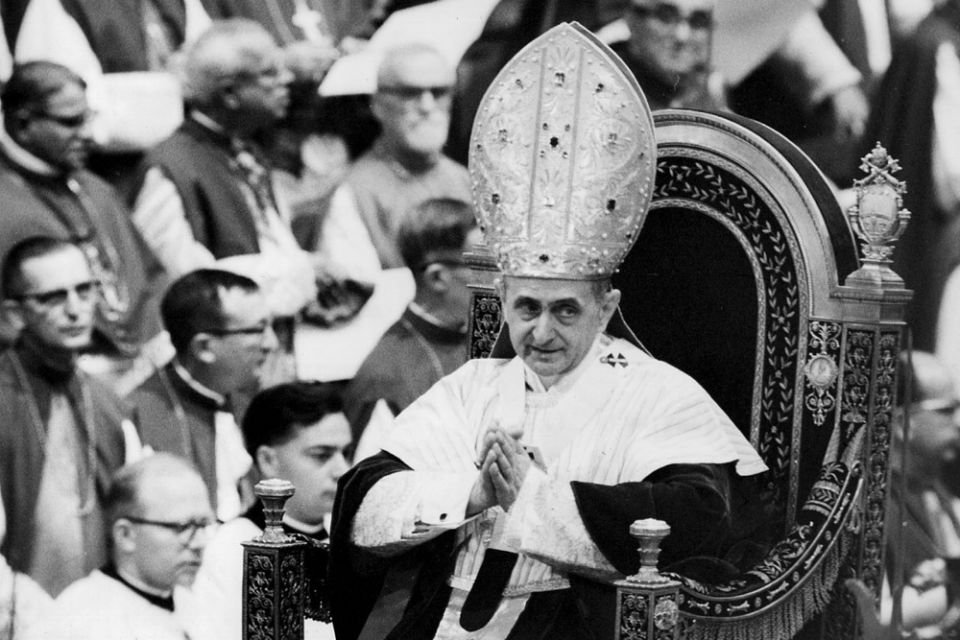

Montini was elected the next day. He took the style Paul VI and immediately announced the continuation of Vatican II. He was genuinely committed to continuing the council along the lines favored by the majority, but felt he had to win over a persistent minority, some of it centered in the Curia, who opposed what they perceived as “unorthodox” views. A key to his papacy was his constant compromise between keeping these reactionaries onside, while attempting to grapple with modernity and the realities of contemporary ministry.

An illustration occurred during the third session in 1964, when he imposed an “explicative note” on the bishops, precluding any encroachment on papal primacy by the doctrine of episcopal collegiality. He knew the minority would never agree to collegiality unless this was imposed. Many bishops were furious.

To regain credibility, he announced at the 1965 session that he would establish a world Synod of Bishops through which he could consult the episcopate. However, the synod’s rules determined that the pope called it, set its agenda and communicated its results. Pope John Paul II turned it into a mere papal rubber stamp.

The period immediately after Vatican II saw the publication of a whole series of post-conciliar documents applying and expanding the reforms of the council. A new spirit of openness spread throughout the church, the vernacular was successfully introduced into the liturgy, and ecumenism flourished. But the failure to reform church structures thoroughly provided opportunities for those who wished to maintain the old values and power structures.

This is illustrated in Paul VI’s attempt to reform the Roman Curia. Sure, a retirement age of 75 was imposed, curial appointments were for five years, the Curia was internationalized and the old Italian career structure was considerably modified.

But the pope faced fierce resistance to these changes, and the most that can be said is that he rejigged the old structure rather than radically changed it. He also insisted on the maintenance of clerical celibacy.

But Paul VI notched up considerable achievements. He built lasting bridges with the other Christian churches and faiths, he traveled widely to promote social justice and highlight the lack of equity that characterized the world. He visited the United Nations in October 1965, passionately calling for peace: “One cannot love with offensive weapons in his hands.”

He also abandoned the detritus of papal pomp and circumstance, such as the coronation triple tiara. He expanded and internationalized the College of Cardinals, and stopped cardinals over 80 voting in papal elections.

The revolutionary encyclical Populorum Progressio (1967) dealt with the north-south divide and the gap between rich and poor. He even recognized that there is a world population problem. The encyclical inspired the 1968 Latin American bishops’ conference in Medellín, Colombia, where the idea of salvation in terms of liberation theology was first expressed. In Kampala, Uganda, in July 1969, the pope stressed the importance of the church adapting to local cultures.

Tragically, it is not Paul’s radicalism that is remembered, but his moral conservatism as defined by the encyclical Humanae Vitae (July 1968). The contraceptive pill had come into widespread use in the 1960s, and under pressure from conservatives to condemn it, he shilly-shallied for several years until, under intense pressure to maintain the line on contraception enunciated by Pope Pius XI in Casti Connubii (1931), he ignored the advice of two papal commissions and eventually issued the encyclical arguing that conception was the natural result of intercourse, and the processes of nature couldn’t be artificially vitiated, so every conjugal act must be open to the transmission of life.