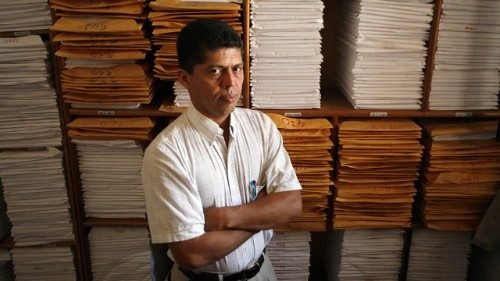

Multinationals have often demonstrated their contempt for so-called Third World countries by plundering their resources. The struggles of farmers and indigenous people against these giants seem doomed to failure. Pablo Fajardo, who went from farmer to lawyer, has turned the tide.

By Manuel Cubías and Jean Charles Putzolu

The words poverty, struggle and commitment are a fundamental part of Latin American history. Many men and women have believed in them, and have given their lives every day, to make them a reality in their countries or in their local communities. Pablo Fajardo is one such case. His love for his people and his land led him to become a lawyer and to defend 30,000 inhabitants of the Amazon rainforest against an oil giant accused of pollution. In 2011, Texaco-Chevron was sentenced to pay $9 billion in compensation for social and environmental damage.

A poor family

Pablo was born in a village on the coast of Ecuador, into a family of farmers living in extreme poverty. This context prompted Pablo’s nine brothers and their parents to look for work far from home, in the Amazon region. It was a whole new world for little Pablo: “The Amazon was full of spirits, whispers, smells and tastes, full of heat, water, insects and animals, in short, full of life”. Later on, he discovered another forest: “The other Amazon was the polluted one”, he says. This contrast changed his destiny.

For economic reasons, none of Pablo’s brothers could study at university. It was poverty that determined who could and could not study. Pablo was able to count on the support of his people, the Capuchin Fathers and of various villages. All of them were an extraordinary, economic and affective support for him.

Migration to the Amazon

There were more opportunities in the north of the country, which was open to Ecuadorians in search of work. At the age of 14, Pablo began working first in a company that cultivated the African palm tree, then for an oil company. In his spare time, he attended the parish led by the Capuchin Fathers. Like many people, he worked hard and I made little money. “I understood that there were many injustices, and exploitation,” he says.

Two years after his arrival in the Amazon, with the support of the parish and the people, Pablo created a committee for the defence of human rights. “We did so because there had been numerous cases of human rights violations against indigenous peoples, women, peasants and black people. They had no one to ask for help”.

Protest of militants for the protection of the Amazon rainforest

Birth of a vocation

Appointed President of the committee, the 16 year-old Pablo went from village to village with the Capuchin fathers, to gather direct evidence of the violations suffered. When he accompanied victims to the authorities to file a complaint, the answer was always the same: they suggested finding a lawyer. “The fact is that, at the time, there were no lawyers who wanted to help us. One day I said to myself, “I’m going to be a lawyer”. But there wasn’t enough money to finance his studies. Capuchin Fathers, Pedro José, José María and Charlie Azcona, had become like Pablo’s second family, and they mobilized many people. Pablo was able to study, to graduate and become a lawyer. But the path proved to be an obstacle course.

The price of compromise

Pablo tells of an episode that marked him: there was an oil company operating in the region that intended carrying out seismic surveys. The workers entered the area, bypassing the peasants and their possessions. Pablo wanted to defend the peasants. The company fired the workers in retaliation, and blamed the young lawyer. Initially, the workers wanted to lynch him, but once they understood the situation, they followed Pablo in the legal battle against the company.

In 2004, after a period of persecution and threats, one of Pablo’s brothers was cruelly tortured to death. Pablo’s family had to move, for safety reasons. For several months, he did not sleep two nights in a row in the same place. Actually, the intended victim was not Pablo’s brother, but Pablo himself. The killers made a mistake. Still, the threats did not end: “Every evening I thanked God because I had managed to live one more day. In the morning I prayed, Lord, protect me so that I may continue to live”.

Group of militants for guarding the Amazon, defended by Pablo Fajardo

The close link with the Amazon

“After thirty years I realize that I have learned, and continue to learn, from the indigenous peoples. They have a lot to teach humanity. The indigenous people of the Amazon are like walking libraries”, says Pablo. In 2003, when the trial against Chevron began in Ecuador, in Lago Agrio, people went out every day to demonstrate. The elderly never wore shoes. A young American who had come for the trial was impressed to see so many people barefoot. In six months he collected five thousand pairs of shoes and sent them to the Indians, who still wouldn’t wearing them. The elderly didn’t wear shoes, not because they were poor, but because the shoe breaks the bond between human beings and the earth.

Polluted water in the Amazon rainforest

The Texaco-Chevron case

In the lawsuit, the natives with their attorneys, brought evidence of land and water pollution with toxic waste, and residues from the extraction of crude oil. The waste caused the destruction of fish, jungle animals, and indigenous peoples. Faced with this environmental massacre, the inhabitants felt helpless because they did not know how to deal with the oil giant. Apparently, even the State failed to protect the rights of the indigenous peoples, or to inform them of the negative consequences of the pollution.

Pablo explains how the Texaco-Chevron case demonstrated a profound lack of knowledge and lack of respect for ancestral peoples. At the same time, the case also highlighted the tenacity, and the struggle of these peoples for their rights. “The important thing is to see how we managed to maintain unity in the struggle. Six indigenous peoples with different languages, traditions, customs, and territories joined forces to fight together”. Many indigenous people were not lucky enough to be able to study. Like Pablo’s father, many could not read or write. They didn’t trust written documents, but they attributed a fundamental value to the given word. When they were little, Pablo’s father used to tell his children: “Paper can be torn, but not words”. Today everything has changed, everything must be written down, documented, signed, and stamped. Without an official document, the spoken word no longer has value. In defending the helpless, Pablo became a bridge between his spoken word, given to the Indians, and the written words of accusation against Texaco-Chevron, documented in austere courtrooms.

Traces of pollution from crude oil extraction

The lives of people and of future generations depend on what happens to the Amazon: “Perhaps many people in the United States or in Europe do not realize what the Amazon means for the world, for the planet. The lives of future generations are at stake”.

The last words of Pablo Fajardo, a farmer who has become a lawyer for his people, are words of hope: “May the whole world listen to us”, he says.